Why did the round house builders of Bronze age and Iron age Britain point their houses toward the rising sun. Was it cosmological or to keep the house dry?

Question – you are to build a round shelter for yourself. It can have walls and a roof but no windows. You can have a doorway but (for the sake of argument) no door.

The following weather is going to affect your house:

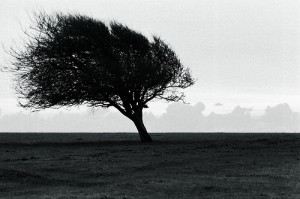

There’s usually a strong prevailing wind from the west or south-west. This often brings rain. Sometimes the wind switches to the north or north-west. This wind is not as strong but is much colder and also brings rain.

Occasionally there is a north-east or east wind. This is again cold but is very rare and is generally dry. Also occasionally there is a wind from the south-east, but this is generally warm, light and dry.

Where will you put the doorways on your shelter?

Ritual in archaeology

In archaeology, when something is dug up that cannot be explained through simple logic it is generally taken to have ‘ritual significance’. So, for example, ‘ritual deposits’ could be things that were put into the ground with bizarre and seemingly pointless care.

Alternatively, ‘ritual alignments’ could be rows of posts of stones set up to point to something that no-one can now be sure of. Indeed, even now there are plenty of examples of people all over the world doing things that really are of no practical use. This blog is ritually significant.

The ritual British round house

There is an increasing belief among many British archaeologists. This is that the orientation of the doorways in British Bronze and Iron Age roundhouses is of ritual significance. This conclusion is due in large part the fact that almost all their doorways faced somewhere between east and south-east, with particular peaks of positioning either directly east (toward the rising sun on the equinoxes) or directly south-east (toward the midwinter rising sun).

The diagram showing round house orientations is taken from a Mike Parker-Pearson and Colin Richards paper, they in turn having taken it from a 1991 PhD thesis by (?) Alistair Oswald (which I’ve never seen).

Due to the positioning of certain household objects found in a few key archaeological digs of British roundhouses, the idea of ritual orientation of round houses has now been elaborated. The orientation of the round houses’ entrances and the placing of items in the houses are now all seen as ritually significant. They are taken to reflect the ‘cosmological’ ‘metaphor’ of a person’s journey from birth (sunrise) to death (sunset).

Discussion

Now I can’t argue with what these archaeologists are currently saying. They may be right or they may be wrong. There are undoubtedly alignments with points of the compass in many monuments, including round houses. What I would be interested to see are how these alignments vary with time, latitude, local topography and local weather conditions. That would truly sort out the details and perhaps answer some of the unresolved questions.

But I find it disturbing that in the recent literature on round houses I’ve found only one author (Anthony Harding) who has mentioned the obvious consideration when orienting the doorway on your roundhouse. And that’s the weather.

A pattern language

‘British’ house builders throughout the millennia must have mulled over the problem of how to orient their houses to combat the weather. Over time rules have undoubtedly been established to sort out the problem.

For example the Scots Gaelic saying “Cul ri gaoth,aghaidh gu ghrian” (which translates as something like “back to the wind, face to the sun”) spells out a Hebridean rule for orienting your home in the high winds of the islands.

So why not something equivalent in ancient Britain, such as “If you don’t want a wet inside*, point your door to mid-winter’s sunrise” or some such piece of folkloric wisdom (*NB ancient people may or may not have been as smutty as you are).

And this is a kind of ritual orientation, what Christopher Alexander, in his classic work of architecture, would call a ‘pattern’.

Interestingly, if you turn this on its head and say “I need lots of wind zipping through this building to get rid of the awful smell,” – for example in a mortuary house – then making the doorway of your building point into the prevailing wind is an excellent solution. Indeed, likewise, always point your hearth toward the air from the doorway if you want a good blaze.

So, to answer the original question I set, the best orientation for your doorway would be somewhere between east and south-east. Give yourself a peanut for being correct.

References

Alexander, C. et al. 1977 A pattern language: towns, buildings, construction, Oxford, pp1171

Harding, A.F 2000 European Societies in the Bronze Age, Cambridge, pp572

The Met Office 2009 Met Office Virtual Met Mast (pdf showing the yearly pattern of wind of Britain), pp11

Parker-Pearson, M. & Richards, C. 1994 Architecture and Order: approaches to social space. Routeledge, pp230

Additional References

Crowther, T. 2011 Shedding Light on the Matter: An Exploration into the Regional Orientation Patterns of the Brochs and Duns of Iron Age Scotland, Assemblage 11, p47-58.

A discussion of Scottish Broch and Dun entrance orientations. These late Iron age Buildings show quite variable entrance orientations, with regional differences in preferred orientation, although overall the most common orientations are to the NE (duns), or E and SE (brochs). The detail (or lack of detail) of the rose diagrams (16 orientations only are recognised) means that orientations tend to be bunched (e.g. all angles between 34 and 56 east of north are considered to be roughly 45 degrees east of north). All the same, intermediate orientations (e.g. ENE) are uncommon, suggesting that builders used a simple division of orientations, aligned roughly at 45 degree angles from N, as is shown in the Oswald diagram. These orientations are SE, E, NE, NW, W and SW. The author goes on to speculate about these orientations being related to sunrise and sunset positions, which seems reasonable.

{ 8 comments… read them below or add one }

Dear sirs,

Please look at http://www.proto-english.org/stone.html

Best regards,

Michael G.

Unfortunately, in this instance both the original author of this piece (Geoff) and the various respondents are tilting at windmills of their own making. None of you are archaeologists by your own admission, and several of you appear to be proud of the fact that you’ve not read much of the literature. That, at the very least, is indeed obvious in your discussions (I might add that these days glorying in ignorance is part of the right-wing, anti-intellectualism of British and American popular life, politics and media). You claim that there is an assumption, and an unchallenged one, of the veracity of the cosmological case for British roundhouses. That is simply just ignorance of the field (incidentally, Oswald’s door orientation paper was first formulated in his undergraduate dissertation thesis! He subsequently published in an edited volume of papers called “Reconstructing Iron Age Societies”, edited by Gwilt and Haselgrove). There are a considerable number of dissenting voices from this thesis and there have been since it was first proposed. Read articles by Rachel Pope if you wish to see something of the counter arguments, although personally I feel these are themselves mostly specious and reactionary (in the conservative sense).

Geoff MPP only opened up his article on this subject by referring to the reconstruction roundhouses of Britian he actually bases his analysis on archaeoligical examples from England and from Scotland. However, I find it interesting that you appear to feel that a discussion of cosmology based upon reconstruction houses is unacceptable and open to ridicule but don’t seem to think that there is anything wrong with other types of knowledge claims of the type being made in Geoff’s web-site and article based on the same reconstructions. I feel this is a return to Hawke’s ladder of inference that asserted that some sorts of knowldege about past human socieites were less knowable than others, with technical procedures, economy and subsistence patterns on the lower more accesible rungs of the ladder and society, politics and ritual on the upper rungs less obtainable. The danger in this logic is it condemns us to consider it unlikely or even impossible to access these realms of past human activity and to think of them as neatly compartmentalised from things like economy and politics, which they most assuredly are not.

For his part, Ned claims that there is an anti-scientific spirit in current archaeology. There is not. In reality a strong anti-‘scientistic’ attitude has developed in contemporary archaeological theory. That is, there is deep cynism surrounding the spurious claims of an earlier generation of archaeologists to be able to provide all of the answers to all of the questions on the basis of supposedly uncovering rule-based or law-like, natural sciences type, predictions of behaviour and reaction applied to human beings. This period of archaeolgical reasoning, the ‘New archaeology’ or processualism (approx’ the early 1970’s to mid 1980’s) was crude, deterministic and psuedo-scientific. It held up science as the panacoepia for all interpretative ills and tended to reify science as an end in itself. The worst excesses of ‘New archaeology’ tended to treat human beings as passive and reactive rather than responsible for actively creating the social, political and economic worlds around them. Indeed, the new archaeologists were somewhat guilty of formulating a type of historical analysis without recourse to society at all, or of a vision of society as merely the strategic canvass over which individuals enacted their own selfish projects. It’s a view of society that would have warmed the heart of Margaret Thatcher given her infamous dictum that society didn’t exist. So for many British archaeologists there is a moral repugnance towards the determinism and functionalism of the processual archaeology project. Note also that the leading exponent of processual archaeology was/is Colin Renfrew, himself a Tory peer in the house of lords, (though himself, in my opinion, a man imbued with warmth and humanity towards others).

A subsequent generation of archaeologists (the so-called postprocessualists) reacted polemically, asserting (or re-asserting) instead the importance of context; specific historical conditions, society, context, human agency and the fluidity of the meanings given to, and leant by, the material world. However, key in this new reading of past human relationships with the material world and each other is a very substantial science-aided panoply of new techniques and analyses. Never again, though, will archaeologists allow science to dominate the interpretative tool-kit of the subject because it is simply not up to the job of describing and explaining the complexity of past human actions and communities in anything like a sensitive and ’emic’ manner that might reflect ancient motivations and intentions. Traditional scientific theory is not nearly sufficiently socially mature (nor are its hopelessly abstracted, reductive, number crunching, socially skill-less [read geeky] proponents) to sustain a sophisticated understanding of contemporary human society let alone that of remotely ancient periods. I offer this by way of corrective to a few of the ill-informed opinions set out here and in the hope that you might start to do a bit of reading before you venture opinions on a public forum such as a the internet. These comments will no doubt be read as arrogance by some and political correctness (ooohh the great bogey item of the Daily Mail level readership!) but I’m actually just whileing away a little spare time, having some fun here with a fair amount of tongue firmly in cheek, and at the same time exorcising a feeling of regularly being genuinely sick to the back teeth of the unfounded allegations levelled at archaeologists and what they are supposed to have said, thought or did, made by people who have never bothered to actually look further through commiting enough time to read what archaeologists have actually said or done.

Dear Martin

Thanks for your comment on the post (which, by the way, is purely my opinion and not that of anyone else). I take it that you don’t like what you read. That’s fine, but let me explain my logic.

I’m not much of a fan of Processual thought. Most of it seemed a bit glib and apt to treat people as animals. Post-processualism has a hard task, however, in that it’s trying to show how people could be culturally complex in prehistory, yet has nothing written by those people to allow them to tell their story. What any good PP archaeologist is surely looking for is the evidence to make a good case for someone’s past thought processes.

‘Ritual’ or religious purpose underlies much of people’s lives both in the past and in the present. People in the past arguably took such things much more seriously than we do. They had a much greater investment in ritual because they saw the rigorous logic in what seem to us to be random acts (e.g. sacrifice). This can be a valuable way of seeing into their thoughts.

People in Iron Age roundhouses undoubtedly imbued many of their actions with such logic based on their worldview. The layout of their houses and the position of their doors may or may not have been part of this. The problem that any archaeologist has is to prove that something ritual, of cosmological significance, is going on. In the case of the positioning of doors on roundhouses I think that these particular researchers haven’t made their case.

Archaeologists have always known that ritual is recognisable when something is done that appears to make little practical sense. If the people of the British Isles had defiantly put their doors on the North or West sides of their houses that would make no sense as the houses would be unnecessarily cold, wet and draughty. That would be a formidable case for a cosmological reason dictating the positioning of their doorways.

However, what the Iron Age house builders did did make practical sense. In the same way, no-one is surprised that people in 19th century Outer Hebrides positioned their doorways to face away from the prevailing westerlies.

Therefore in this case to try to justify a particular cosmological view of the British Iron Age universe based on the positioning of house doorways is exceptionally hard and requires other evidence.

This is, I suppose, a scientific approach, in as much as Ockham’s Razor applies. Any additional explanation of the positioning of doorways is currently unnecessary.

best wishes

Ned Pegler

Hi Ned,

Good to hear back from you. I am indeed the Martin Carruthers of Orkney College UHI. Thanks for taking the time to discuss the piece and giving me your response to my own comments. Sorry for my delay in replying to you! This is due to how busy we are here up in Orkney! I’m glad you replied as I appreciate the opportunity to state that I am very supportive of the kinds of interests that you bring out in your web-site, including examinations of the ‘practical’ elements of ancient structures, and indeed of experimental work of a variety of kinds.

I intended that my comments addressed both you the original author of the article and then the various comments that followed, although I’m afraid that at one point I think I confused the names that I was seeking to respond specifically too! I thought that the replies that you received to your piece from other commentators were largely supportive of your premises outlined in the article and so I’m afraid I found it all a bit of a ‘love in’ on the bashing MPP (etc.) front, and thought some redress might be worthwhile/interesting. Sorry, also, if it was a bit ranty but you see I so often feel the need to bite my lip in conferences and the like, and although you were keen to express that you thought that the cosmological work variously undertaken by Oswald, Fitzpatrick, MPP, Giles at al seems to have captured the ascendancy I have to say that is not my experience as an Iron Age specialist attending conferences and meetings across Britain and beyond. I believe that it is still the case that the vast majority of professional archaeologists are highly cynical and not a little sneering about roundhouse cosmology and that gets rather draining when you’re trying hard to assess the utility of these ideas with an open mind, including in excavation as I am currently. I certainly feel that most of those who hold the purse strings in archaeological circles is not favourable to these ideas at all, and those money-conferring institutions are in fact still quite reactionary in academic and political outlook. So I’m afraid that when I read your piece, which to some extent bemoans the absence of a critique of the roundhouse cosmological concepts it rather grated because I’m afraid that’s simply not the case (in academic work check out Leo Webly or Rachel Pope, while in my experience most archaeologists in the National Government bodies such as HS and EH are massively antagonistic to cosmology, and certainly none of research funding bodies (research councils either AHRC or NERC) give out money on the basis of a cosmologically-informed research design. So it is extremely disturbing that your relatively negative reaction to the cosmological concepts is posted with the tone of a lone and marginalised voice when, in my view, your view is more often shared actually by the centre-ground within archaeological power-circles. The hegemonies preside over a situation where cosmology and indeed most of ‘post-processual’ thought generally does not lie at the centre but on the margins. Therefore I feel that, whether wittingly or otherwise, your piece only serves to confirm the view held by those in the power structures (and perhaps more disturbingly those who seek excuses not to pick up a book on archaeological interpretation and see what is said there for themselves) that cosmology is not worth consideration.

I would take issue with your suggestion that PP archaeologists are trying to see into the thoughts of past individuals. A strong strand in the philosophy behind PP-ism draws on work that suggests that such empathy, even in relation to individuals that one might share an office or a house with in the present, is a phantasm and cannot be securely known. Here I’d take John Barrett’s line that we shouldn’t be trying to see inside the mind at all, but simply better understand the historical and social/cultural conditions that framed the opportunities for people’s intentions, plans, projects etc. The whole point of PP archaeology indeed, is to recognise that it is impossible to recover the internal mentality of past individuals. Indeed, any such aim sounds rather more like the objectives of cognitive-processual archaeology with it’s interest in psychology and the aim of recovering universal trends in the human mental processes (a futile and reductive aim in my view). So in this respect, at least, I’d actually say that PPism is practicing better, more mature, more sober, science than Processualism is!

I would also take issue with the definition of ritual that you evoke and this gets to heart of what I’d say is archaeology’s frequently impoverished tool-kit for examining ritual (and please be reassured I’m not implying, patronisingly, that you are similarly impoverished!). Of course it is somewhat of a running-joke that whatever the archaeologist does not understand is immediately consigned to the realm of ritual, and sadly that is still often the logical process of many. However, this is an absolutely wrong-headed and waek view of ritual. I would much prefer if more archaeologists took a long hard look at ritual and decided to be a bit better at reading around anthropology, sociology and the history of religion for inspiration. The work of Maurice Bloch (‘Prey into Hunter’ and ‘Death and the Regeneration of Life’), Humphrey and Laidlaw (‘The Archetypal Actions of Ritual’), Catherine Bell (‘The Ritual Process’) and Bruce Lincoln (‘Emerging from the Chrysalis’) are all stunningly mature and fascinating insights into ritual, which all archaeologists would do well to check-out. The point I would make is that in these analyses ritual is a form of social practice rather than a static label to apply to types of place, sites, landscapes or artefacts and to that extent ritual can very often be embedded and suffused in the everyday (which is very pertinent to IA roundhouses). In this conception of practical (that is: practice-based) ritual, any object or part of the material world may take on a ritual significance according to the context that it is deployed within so ordinary items or places can be drawn into ritual action for a moment in time and indeed they may be spewed out the other end back to the normative. Now this is simultaneously problematic and an opportunity for archaeologists. problematic because it means that identifying the residues of ritual practice/behaviour in the archaeological record is a very much more complex pursuit than simply sweeping up what is left after we’ve imposed a normative attribution to the bits of excavated remains that we think we can understand, and pouring them into the ‘ritual dust-bin’. The opportunity bit comes in that this active view of ritual frees ourselves up from the bogus dichotomy of ritual versus practical or domestic. Therefore ritual and social behaviour are potentially immanent in all aspects that we encounter in the archaeological record not simply the bits we don’t understand. An article (Ritual and Rationality) by Joanna Bruck deals with some of this, which I don’t entirely agree with but it is interesting on the history of the use of ritual in archaeological interpretation.

A final, more specific point is in relation to your comments about the roundhouse entrance orientation. To quote from you: “if the people of the British Isles had defiantly put their doors on the North or West sides of their houses that would make no sense as the houses would be unnecessarily cold, wet and draughty”.

Well certainly in at least one region of the British Isles; the Western Isles of Scotland, that is indeed exactly what many brochs do. There a significant number of brochs turn to face the diametrically opposite direction from that of E to SE. No less than MPP and Niall Sharples have reflected on the fact (see ‘Between Land and Sea, Excavations at Dun Vulan, South Uist’ pages 350-354) and they interpret this as a demonstration on the part of broch-builders that in reversing the norm they were expressing mastery over the natural and cultural world, including marking differential status between themselves and the contemporary households in the wheelhouses which remained E-SE-facing.

Apologies for the long reply but your comments deserved a fulsome reply and the topic is dear to my heart!

P.S. yes I’ve been involved in the Ness of Brodgar site up here, which I suspect is the one you’ve heard of- it is a smashing site! There are plenty of others that we’re working on as well though, including my own research excavations dealing with a very big broch and settlement on South Ronaldsay. If you’re interested I can send you some web-links.

Best regards,

Martin

Dear Martin

Thanks for the extensive reply. Your points are well taken, and certainly highlight my ignorance of the topic. I guess I’ve moved on partially from views I held when I wrote this post, although I’m still no better read. Archaeology, as all subjects should be, seems to be a very broad church and, personally, I’m inclined to believe that most views should be able to be expressed. What seems to be a frustration for people at both ends of the academic spectrum is how closed the academic debate in the centre is often allowed to be, hence both Geoff’s and your frustrations. Without that broad debate things get stuck.

My little, ranty blog here was really just set up three years ago to get ideas off my chest, so that my partner, Steph, didn’t have to hear them endlessly repeated at bedtime. It’s like I can reach some sort of endpoint with my thoughts rather than them going round and round my head. I had dreams of having the kind of discussion that you’re allowing me here with serious-minded people, but soon realised that the internet wasn’t like that. I do like to research the articles I’ve written but, living in Swindon and unaffiliated, I can’t afford to read many of the papers or books out there, so my ideas are undoubtedly half informed or even misinformed. If you have any pdfs or weblinks that you want to put my way I’d be more than happy to read them.

By the way, on the subject of Brochs I don’t know much but I’m sure I remember talking to a friend of Ian Armit’s years ago (I had a copy of Ian’s book on the Archaeology of the Outer Hebrides, but I left it out in the rain in South Uist so all the pages turned into one mega-page). Anyway, this friend said that Ian had discussed the idea of Broch’s being like an enormous thermos flask or something, using the double wall as a kind of insulator or heating system… I can’t remember which. Is this of relevance to the siting of the doorway? On second thoughts I guess not.

Sorry. I’m rambling now. I suspect that I have a million questions on the Orkney dig too, but they might have to wait.

best wishes and thanks once again

Ned

Dear Martin

As a further comment, I notice a recent paper by Thomas Crowther, which refutes MPP’s suggestion that most of the Outer Isles’ Broch entrances were oriented to the west. Although a significant minority faced W or NW, the majority faced either NE or E. Overall, however, it seems that there’s quite a scatter of entrance orientations, making a simple cosmological model tricky and perhaps suggesting that local conditions were significant. Just a thought, anyway.

Ned

Good article.

MPP’s stuff about roundhouses is just peeing in the wind, looking at the ‘cosmology’ of reconstructions! Architectural theory is fine in a real space.

Craft and building traditions often develop meanings and symbolism never originally intended, and these change with time and culture. Religions often appropriate traditions, and adds their own layer of meaning.

I think, that to imagine we can understand these meanings in two and a half thousand year old structures, for which we have only their foundations, is a intellectual conceit.

Here in the North Pennines most farms face east.

Dear Geoff

Thanks. I think it’s just fashion and, currently, fashion in archaeology is anti-scientific. This is not necessarily bad, but without good evidence, all of the current ideas are easily knocked. What concerns me really is the lack of criticism from other archaeologists. The idea of cosmological alignments in houses has mushroomed in the last few years and it’s largely based on the work of just a couple of authors. In geology, my own field, I saw it happen with something called sequence stratigraphy. Unfortunately, most people are uncritical. I certainly deserve to be knocked for some of my ideas but, happily, I don’t have that much influence as not many people are reading this.

love Ned