A review post outlining three main methods of language swapping: 1) Biggest language wins, 2) Richest or most violent language wins (this is helped if languages are similar), and 3) Everyone’s second language wins.

This post is aimed at anyone who’s interested, although it comes from a particular discussion between me and others about the spread of the Indo-European languages.

This post is aimed at anyone who’s interested, although it comes from a particular discussion between me and others about the spread of the Indo-European languages.

The question is simple; are there any generally accepted laws of language swapping where a geographic region changes its main language? Probably. Have I found any in the literature? No.

Part of the problem seems to be that language shift (the swapping of one main language for another by a particular bunch of people) is extremely politically loaded, coming with the baggage of colonialism, neo-colonialism, oppression of minorities and loss of diversity.

To be harsh, I’m not looking at any of this here. The remainder of this post is aimed at putting forward the main arguments I can find from various academics for why geographic areas swap their main languages. Here is what I’ve found.

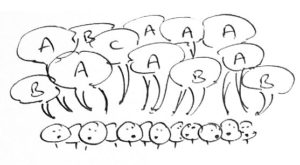

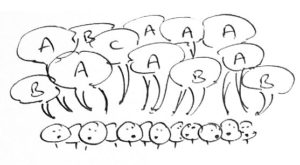

Population dominance – Go with the herd

In this model a population coming into a new area brings more speakers of its (main) language into that area than the speakers any other language group already present in the area. This results in these minority linguistic groups showing language shift to the language of the incomers.

In this model a population coming into a new area brings more speakers of its (main) language into that area than the speakers any other language group already present in the area. This results in these minority linguistic groups showing language shift to the language of the incomers.

The methods of actually achieving linguistic dominance have historically included:

- Immigration – the arrival of large numbers of new people into an area (e.g. of 17th-18th century English speakers to the colonies of America and Australia, or of 18th century Han Chinese farmers into frontier areas);

- Displacement – forcing an existing population to leave the area (e.g. of 20th century Poland and Ukraine by the Soviet Union and Germany);

- Population fall – usually caused by disease introduction, famine, genocide or birth rate decline (e.g. 15th to19th century introduction of European diseases into the Americas, Australia and South-western Africa, the 19th century potato blights effect on Gaelic-speaking western Ireland.)

It would have been good to separate these methods. However, they often go hand in hand. For example, the collapse of the American population was caused by immigration of Europeans bringing disease. Also, the aggressive displacement or extermination of one population by another may be to create new territories for immigrants to settle. It also needs a large population to carry out the displacement effectively.

Importantly, in this model population replacement does not necessarily mean language replacement. Short time scales are essential and language shift happens faster the higher the rate of swamping of minority languages. A slow, steady stream of immigrants over generations may eventually swamp the genetic signal of the original inhabitants of an area, but each small batch of immigrants will come as a minority, switching its language to the language of the majority, the old language of the original inhabitants (this has just been demonstrated nicely in the case of Vanuatu).

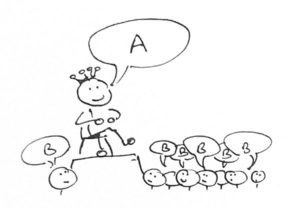

Elite dominance – Swap or lose!

This is the opposite of the model above – language shift to a minority language by the majority population of a region. It results when the minority language as used by the elite of society. It has been a significant cause of language shift in the last one to two hundred years. There are two main ways that this has happened:

This is the opposite of the model above – language shift to a minority language by the majority population of a region. It results when the minority language as used by the elite of society. It has been a significant cause of language shift in the last one to two hundred years. There are two main ways that this has happened:

Imposition

In this, people are forced by a physically strong elite to learn their language under threat of violence (this includes the education system). It has occurred in a number of countries since the 19th century, including the imposition of English in Wales and Ireland, of Spanish in Latin America and of Turkish in its SE Turkey.

However, it should be pointed out that forcible methods are usually effective only in small geographical areas (up to around 30,000 km2) controlled by neighbouring, large, organised and highly literate states or empires (this is the case with the change from Arabic to Turkish in SE Turkey, or of Scots Gaelic and Welsh to English in the UK, or of Breton to French in France, or of Slovene to German in Austria, etc).

On the other hand, such forcible methods are not known to have been successful where a resident minority has tried to impose its language on the majority of people in a larger area (notable failures are of the Anglo-Normans in 12th century England, the Swedes in 19th century Finland). Many minority elites in a region haven’t even tried, rapidly adopting the language of the subject people.

(There may be an interesting example of Medieval enforced language change in East Prussia, where the German ‘Teutonic Knight’ monastic elite appear to have been reasonably organised and successful in changing the local language from Prussian to German between the 13th and 17th centuries. However, local population loss from plague, together with German immigration, may also explain this language change.)

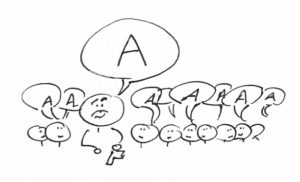

Social betterment

In this, people wish to climb socially, and learn the language of the elite as well as having their children educated in the new language. Historically, this can be argued to be the case with the adoption of English (either UK or US) by various cultures since the 19th century, including by many Maltese and by city dwellers of India. The same can be said of the adoption of French in the cities of some of France’s ex colonies and even in some former British ones (e.g. Sierra Leone).

In this, people wish to climb socially, and learn the language of the elite as well as having their children educated in the new language. Historically, this can be argued to be the case with the adoption of English (either UK or US) by various cultures since the 19th century, including by many Maltese and by city dwellers of India. The same can be said of the adoption of French in the cities of some of France’s ex colonies and even in some former British ones (e.g. Sierra Leone).

However, historically it is urban populations or populations of small islands that have tended to adopt the new languages, although they often stay bilingual (the adopted languages are, at least initially, linguae francae – see below). The population of the greater countryside does not adopt these new languages. This may now be changing. The advent of communications technology even in rural areas means that prestige languages are causing language shift in these areas too (this is clear with the loss of Gaelic and Irish in Scotland and Ireland).

I suspect that we shouldn’t underestimate the effects of mass literacy and the expectation of literacy on the success both of these methods in the last two hundred years. The increasing requirement to be able to read, whether signs or legal documents, means that a knowledge of the written language has become necessary to many inhabitants of modern nation states. If this is to cause major language shift it’s necessary for a large proportion of the population to be able to read. Such effects would not have been significant in earlier, less literate ages or with less organised states.

Making it easier – related language adoption

A more speculative idea is that elite languages are more readily adopted when they are not too dissimilar to the existing language, as the original population find it relatively easy to change their language.

A more speculative idea is that elite languages are more readily adopted when they are not too dissimilar to the existing language, as the original population find it relatively easy to change their language.

In this case, the new language introduction could be by an incoming minority, albeit a dominant or prestigious minority, as above. However, the resistance to language shift is decreased.

Nick Ostler argues that this would explain the spread of the Arabic language to the Middle East and North Africa from the 7th century AD onward, as both already spoke Semitic languages (e.g. Aramaic and Coptic). The corollary to this is the failure of the Arabic language to take hold in Iran (where people spoke unrelated Iranian languages). It may also explain the adoption of Latin by Celts in western Europe during the Roman period (see further discussion below) and of Turkic languages by Mongols in the medieval period.

More historically, can this method explain the replacement of Byelorussian by Russian (both closely related Slavic languages) during the 20th century. I don’t know. It would be nice to have more certain examples of such a mechanism.

International chat – adoption of the lingua franca

Many people throughout history have, in fact, spoken more than one language: one at home, and at least one to less well known people. This is quite normal. We live in an age where many people speak English as well as their home language.

Many people throughout history have, in fact, spoken more than one language: one at home, and at least one to less well known people. This is quite normal. We live in an age where many people speak English as well as their home language.

These languages are, as above, often used to get on in the world as they allow communication with other groups in trade, education and technical discussion. Apart from modern English, there are many other historical examples, including Sanskrit across Southern Asia, Greek on the western Silk Road, Swahili in West Africa, Aramaic in Iran and the Near East, Medieval Latin in Europe, German in the Baltic and French in Western Europe.

However, it should be pointed out that these are second languages. As such, they often fail to replace the home language, and their long-term consequences can be ephemeral. This is clearly the case with Sanskrit, which is now extinct with no descendants, despite its widespread use several hundred years ago. The same can be said of Medieval Latin. Arguably, if America fades and China rises the incentive for an internationalist to swap their second language to Mandarin will rise too.

So are there any cases where the lingua franca has been adopted. For example, what about Ancient Latin or Arabic?

Ancient Latin is a most interesting case in that it appears to be a lingua franca which was adopted, in corrupt form, as the first language in central and northern Italy, the Iberian Peninsula, in France and among the Vlachs (‘Romanians’ in the broadest sense) of the Balkans. However, this needs to be analysed carefully.

In the case of Italy, Rome’s dominance of the local region, both in terms of elite power and population (due to establishment of coloniae), may have caused language shift in locally to Latin. This could be an example of population dominance or elite dominance of a small local area.

In the case of the Vlachs it is possible that East Romance languages result from the settlement as farmers in the Balkans of predominantly Italian legionaries, who then maintained their identity as a mountain people after the migration period. Alternatively, polyglot groups of settled legionaries from all over the empire (possibly together with some locals) might have used Latin as a lingua franca between them when they were settled in the Balkans. As more of them spoke Latin than anything else this became the dominant language, even though it was very few people’s first language.

On this basis, the adoption of a lingua franca as a first language may well be the result of linguistically fragmented groups in a region adopting a language of communication simply to unite them.

What happened in France and the Iberian Peninsula to cause language shift from the various original languages of these regions is more difficult to establish (as it is with Arabic). Firstly, it’s not known how uniform the languages of these areas were before their incorporation into the Roman Empire. Caesar suggests that large parts of France spoke Gaulish, although other languages spoken in France included Belgic, Greek, Basque/Aquitanian/Vascon, Iberian and Ligurian. In Spain Iberian, Celtiberian, Lusitanian and Gallaecian/NW Hispano-Celtic are all recorded, whilst Basque must also have been present.

Second, it’s not known how long it took for the language to shift to ‘Latin’. It’s also unknown what proportion of Latin-speaking (either as first or second language) settlers migrated to these regions. Subsequently, there was significant population loss and a large minority of Germanic speakers settled both regions. Therefore the adoption of Latin as a lingua franca in a linguistically fragmented landscape may be correct. However, it’s almost impossible to be certain.

Interestingly, linguae francae, due to their importance in written communications with other language groups, are precisely the ones that we know about historically. The languages that the majority of people daily spoke in Bronze Age Sumer, Iran, Greece, Crete, Anatolia, etc, may have been Sumerian, Elamite, Mycenaean Greek, ‘Linear A’, Hittite or Hurrian, but they may not. This makes determining ancient language shift so much harder.

Could the necessity to use such written languages have ever caused language shift? The answer may be no for peasant societies of the past. However, the effects of communications aided by states/empires, technology or both, mean that second languages can become increasingly important in daily life, not just in long-distance trade or exchange of ideas. Such an effect can be seen clearly in modern India, where many people use the neutral English in preference to Hindi in their communications, both written and spoken, with people outside their own linguistic groups. Whether such linguae francae will become first languages for the majority of such vast regions as India is unknown.

Combinations of effects – e.g. Hebrew

There is no reason why more than one of these effects cannot combine to cause language shift. Perhaps the classic case is the resurrection of the use of Hebrew, especially in Israel, from the 19th century onward. This was effective for at least three reasons.

- In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Hebrew could be used as a written and spoken lingua franca between disparate Jewish groups in Europe and the Middle East as chances for communication improved between them due to technological advances.

- When Jews migrated to Palestine in the 20th century these incomers were all minorities, speaking many different first languages, and needed a language of communication between them. In this they shared Hebrew.

- The Israeli state, once formed in the mid 20th century, put its weight behind the use of Hebrew in education at the expense of other languages.

There’s no reason to believe that other combinations of effects couldn’t result in language shift in the past, now, or in the future.

Speculations in Prehistory

So far, so historical. Unfortunately, many of us on blogearth want to understand why language change happened in Prehistory. Frankly, most of this revolves around our fascination either with our chosen national identifiers or with Indo-European origins or, often, both. What troubles me is that none of us seems to take the trouble to find out what can cause language shifts either in the present or during well recorded history.

So one particularly prevalent view, as expressed by many enthusiasts, is that prehistoric warrior elites have caused language changes. This is, essentially, a machismo view of prehistory, either despaired of (e.g. Marija Gimbutas’ view of the coming of the Indo-Europeans to peaceful ‘Old Europe’), celebrated (e.g. Madison Grant, Gustav Kossinna or even the Eurogenes Blog (David Wesolowski has taken exception to this slur and I’m happy to retract it), or a cause of mental confusion (e.g. David Anthony).

And yet the historical evidence for language change resulting from nomadic warrior elites is still scarce. Eastern Europe suffered repeated waves of horse-warrior incursions after the fall of Rome. This includes the Alans, Mongols, Pechenegs, Bulgars, Cumans, Magyars, Avars, etc. Some of them went on to rule the areas they invaded (e.g. the Bulgars and Cumans). However, only one of these groups, the Magyars, left a linguistic legacy.

As stated by Jean Sedlar, the success of the Magyars was probably due to their arrival in a sparsely populated area (the Hungarian Plain), meaning that they may have been in the majority there (the previous immigrants to the area, the Avars, were also of eastern origin according to the limited genetic data, and possibly spoke a related language, which perhaps helped).

On the other hand, the slowly migrating mass of Slav peasant farmers, not on horseback, who settled a depopulated Eastern Europe in great numbers from the 6th century onward, have left a huge linguistic legacy, despite often being ruled over by horse-riding elites (e.g. the Bulgars and perhaps the Croats) speaking other languages.

So this appears to be a failure of elite dominance and a success for population dominance. The reason for this is probably simple; nomadic warrior elites were not that organised and their populations not that educated. Furthermore, they were not part of a neighbouring majority.

So maybe there were (possibly horse-riding) elites in the Bronze Age. They may even have sired many children and left their disproportionate legacy in Y-chromosomes (as seems quite likely). And yes, they probably did sweep into India and Europe and Iran and Anatolia during this time. But, from the point of view of language change it’s not them that matter. They could speak any languages they wanted, be they related to Iranian, Finnish, Turkish or something now lost. It is the slow, vast, uncelebrated swarms of peasant migrants, wherever they came from, who probably caused the language shifts.

References

Amorim, C.E.G. (posted on bioarxv 20-2-2018) Understanding 6th-Century Barbarian Social Organization and

Migration through Paleogenomics, pp27.

A sketchy bit of data so far, but which suggests considerable Italian migration to Central Europe during the late Roman period. Though definitely a minority, perhaps there were local areas where Italians were in the majority. Additionally, a couple of samples may (!!!! too little data) suggest a notable influx of foreign genetics into the Hungarian Plain during the Avar period. Two Avars do not make a population shift, however.

Heggarty, P. 2015 Prehistory through language and archaeology, In: The Routledge Handbook of Historical Linguistics (Bowern, C. & Evans, B.), 598-626.

Very pro Colin Renfrew’s Anatolian PIE theory, but a good overview of the mainstream view on language shift.

Ostler, N. 2005 Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World, Harper pp614.

A really good source for many of the ideas in this post, concentrating on history.

Posth, C. et al. 2018 Language continuity despite population replacement in Remote Oceania, Nature Ecology & Evolution (online).

Appearing after I started writing this, it didn’t phase me as much as it might have. I’ve only seen the summary here.

Sedlar, J.W. 1994 East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500, Uni. Washington, pp556.

Source of information on language and changes in central Europe during the migration period.

{ 12 comments… read them below or add one }

Thanks for your post.

Just a couple of side-notes.

The US Census published maps that seem to say that the majority of people in the US are not descended from English speakers. Kind of striking is the large number of people in the mid-west who report descending from Germans. Historically, of course, all those German immigrants weren’t particularly subject to a “dominant” culture. In some cases, they were the local majority. There was a very calculated effort among the educators and church leaders to move to English early on. The “identity” switch that came with language change was strongly motivated by economics.

So here you have a “massive” migration where the migrants adopted the host language without being dominated much I suspect. And despite the strong cultural identification that came with the language.

I wonder how much language identification mattered back in 6000 ago in Europe? Before schools and flags and propaganda. I would think the economic advantage would be in being able to speak with people who did not speak your language and that would be more important. A common language would be a big advantage in many ways. A neutral language not favoring anyone more than anyone else. Maybe early indo-european was that neutral language?

Dear Steve

Thanks for the constructive comment. It’s interesting to speculate on how much the adoption of PIE as a secondary language can account for the variations seen in the major branches of Indo-European. Either way, the spread of Indo-European is highly likely to be part of a migration into ?depopulated areas, like the NW European settlers in US mid-west were. What’s also interesting is to speculate on how many different language groups took part in the IE migration or how varied those languages were.

Once established, it’s questionable how much incentive there was for the ancient migrants to have kept a secondary language unless, as you say, they all spoke different first languages. I don’t know how diverse the US settlers were in any particular area (e.g. Swedes & Germans and English), but the communications wave that rapidly followed them and kept them in contact with the east was not matched by the ancient migrations of Europe.

I’d love to have more info on this if you have any.

best wishes and season’s greetings

Ned

Another sidenote (ha!)

https://slate.com/culture/2014/05/language-map-whats-the-most-popular-language-in-your-state.html

Fascinating article on current “second languages” being spoken in the US

How much is using these languages a matter of “identity”, practicality or just being a first generation immigrant? I once heard a guy who was in the peace corp somewhere on the border of several South American countries including Brazil — he said what he learned there was that if you could speak all of the languages spoken, you had the power. I’m a kind of a hyper-functionalist about language. It’s about communication (or preventing communication) — especially back then before schools and writing and politics.

Happy new year!

Dear Steve

Happy New Year to you!

I notice that the third languages are in the <0.5% end of things. I guess that they have little to no chance of long term survival except in tradition or religion. Spanish is big in the southwest but less, and often much less in more densely populated states of the east, and has little chance of holding on as a language in these unless migration increases hugely or government policy changes.

Here is Britain we have about 8% of people speaking another first language than English. Of course, there are obvious additional languages like Welsh (Cymraeg) and Gaelic in Wales and Scotland, but these only account for a small part of the statistics. In England alone several percent of the population in rural areas speak other European languages (often Eastern European). In urban regions the percentage is generally higher. In the Midlands and South of England up to 30% of the urban population speak other first languages than English (mostly from the Indian subcontinent and Eastern Europe). Except for odd cases such as Leicester and some parts of London, these are made up of many different languages, all of just a few percent. This is the result of recent immigration to Britain (say the last thirty years). There will be exceptions, but those languages have a dim chance of any survival in Britain in the next fifty years unless they are continuously replenished. This has always been the case for minority immigrant languages, either here or in the US. This is, I guess, due to the overwhelming advantage to all these minorities of speaking English, not just in furthering careers and education but just in communication between them and other people. This is particularly interesting as some of these groups do not get on at all (historically, think Irish and Italian settlers in the US). Whatever, I really don't know how much advantage there would be in speaking both Romanian and Urdu in a place like Sheffield, except if you worked as a nurse or in some other care profession. Generally, these are poorly paid jobs.

best wishes

Ned

thanks for the reply, Ned — still just a sidenote

Someone suggested to me that English as a second language might have more speakers on the planet than as a first language, Don’t know if that is true, but I’ve been surprised a bunch of times by someone speaking English where I don’t expect to hear it.

Don’t know about Romanian and Urdu, but there was a well-known Congressman in Brooklyn who could speak Spanish, Hebrew and Polish depending on the rally he was at, and that sure got him votes. He was “one of us” no matter who “us” was,

The point about the US second language was that most are, as you say, vestigial. But it is interesting to see German still there. The first German migrations are actually older than the US and I think it shows how a very large migration came to chose to switch languages — nobody really forced them, Compare the still adamant French speakers up in Canada.

But here’s a point worth considering — where’s the German substrate? Hard to find,

SO If Corded Ware rolled into central Europe like the American Germans, maybe they adopted their IE afterward? Maybe that substrate in Gemanic is whatever CWC was speaking before they changed to IE? Just a side bar, 🙂

Hi Ned, here a I come to my second point: horse-riding! Two posters from Davidsky’s blog have honestly assured me that horse-riding is not attested before 1000 BCE on the steppe. They imply it all began with the Scythians. From here on it’s all well-documented, complete with bits and harnasses … But it seems to be a bit late (not to say far too late to me). But indeed (likewise) Slav horsemanship is poorly attested in their formative ages.

To this I have only this to say: native American horsemanship is totally unattested by archeology! No bits, no harnesses, no nothing! Just horses. So no evidence of Indians riding horses?? That’s right! No archeological evidence!

As to the Slav languages I’ve read on the Internet it’s a very young language, not to be compared to Sanskrit, from which it is separated by some 2000 years. And then there’s this strain saying that Slav traditions correspond to Sanskrit traditions to such a degree that it seems feasible to assume a pre-ante-proto-Slav (to coin a monstrous word) that witnessed the formation of CWC and – couple of centuries later – Sanskrit.

In fact, if one follows the model of the European languages deriving from late PIE-Steppe-dialects, Celto-Italic started with R1b groups in Hungary, whereas the northern branch (Slavic, German) were R1a dominated, as was Sanskrit.

Where des this leave Greek? Armenian? Anatolean? Search me! I got nothing! Only the first two are definitely Steppe …

Dear Jaap

Just to be clear here, you’re talking about archaeological evidence in North America for horse riding after horses were reintroduced by the Spanish in the 16th century. Post-Columban North America is, indeed, a fascinating example of the invention of a nomadic ‘barbarian’ lifestyle which took no more than a couple of hundred years to catch on and recreated all of the frontier world so well known from Eastern Europe.

To explain my comments about Greek and Armenian, my position was to argue the possibility of Indo-Iranian, along with Greek and Armenian, being from somewhere near the southern Caspian Sea. However, once you accept that Indo-Iranian is essentially part of a back-flow of steppe peoples from eastern Europe, then its relatively close cousins, Greek and Armenian tend to look like they are part of that same tradition. Trying to put their origins in Anatolia or the Caucasus then looks like rubbish. The case for Anatolian is less clear, but perhaps unimportant. It’s origin is somewhere either north, south or in the middle of the Caucasus.

Either way, even if it’s all over it was fun to research, and that’s more important than being right.

love Ned

Hi Ned! Congrats to a well-considered response to a provocation. Please understand, that’s all it was: a playful juvenile bulling around. It has evolved into a habit, and one can understand why: the painstaking polite scientific procedures do tend to bore the shit out of people when the truth is in plain view! However!!

The plain truth is not in plain view for everyone. Needs careful explaining. Moreover the juvenile mind is not always aware of all the intricacies involved in dealing with the ‘plain truth’. Davidsky knows what he wants, what he wants to convey to people, and he couldn’t care less as to other agendas!

It’s a fight about people’s attention! A bluff! Nothing more! Maju is suffering like you are (cf his penultimate post: a rather humourless ‘satire’).

Basically this is what the young ones are up to: winning in the polls! This is a mindlessness that is better ignored completely. All the more so as Davidsky is doing a great job, just as you said in your reply. But he’s also a moron in need of recognition, someone who needs more than just doing a good job. There’s no real reason for someone like you to be at the receiving end of this delinquency, so please don’t be!

Please go on being who you are. Please go on doing what you do! You’re good! Stick at it!

Thankyou

Are you mentally ill or what? The conclusion here is that cattle herders caused language change, not the chariot warriors who came after them from the steppes.

http://eurogenes.blogspot.com/2018/03/main-candidates-for-precursors-of-proto.html

Kindly pull your head out of your behind and take a breath of fresh air before you start randomly insulting people. The door swings both ways.

Dear David

Thanks for your robust response.

Technically, I think what you said is fair. Also I think comparing your view to Madison Grant is a bit harsh. Furthermore the horse aspect is irrelevant and I think I’ll probably remove it from the post. So you win there.

You’ve taken quite a strong view recently that language and genetics are intimately connected for these ancient people, which I think is reasonable (athough see the paper on Vanuatu above). However, you use the word ‘invasion’ frequently in your posts (see “The Indo-Europeanization of South Asia: migration or invasion?” from last July, a post which, incidentally, also talks about ‘ruling classes’).

I have no doubt that invasion and migration happened during the Bronze Age in Europe and India, and that there were ruling classes. The point I’m making in this post is that migration is, in my view, the key to this ancient language change in both of these cases, not invasion. If you put too much store on invasion you end up sounding like Kossinna or Grant. There are, as David Reich has pointed out, other explanations for migration, including population failure and the influx of new settlers to an area.

Either way, we still await news of ancient genetics in India, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the steppe influx view is proved right. However, I also wouldn’t be that surprised if it turned out to be less simple and involve multiple streams of immigrants.

The second thing I’d say is that your email was breathtaking and I finally understand why people talk about cyber-bullying and its effects on the receiver. Your comment made me quite shaky and I took quite a while to sleep that night. This is not good for people. Your website is interesting, informative, a good source of new information on the latest ancient genetic research. You also make all of your analyses freely available, which is commendable and scientific. However, you currently don’t behave like a scientist, but rather like a cyber-bully to many of your fan-base, and perhaps you should give this some thought when you write in reply to their comments, either on your site or theirs.

I hope that you’ll give this some thought if you ever read this reply.

best wishes

Ned

Thanks Steve

It may well be true about English as a second language. It is big in India, for example, due to the multiplicity of regional and unintelligible languages across the sub-continent. It would be interesting to see what happens to it in the future and whether it replaces some local languages. However, the influence of the substrate on this English is huge. It used to be the subject of many ‘hilarious’ jokes about Indians in England, but we’re all too sophisticated for that now no-one would never do this anymore…

A very fair point about your congressman.

Funny, but I don’t know much about German migrations to the US. I knew about the Dutch, but I guess that these early migrations had quite varied dialects, including Dutch. Were they mutually intelligible? Is the German that survives quite unusual? The only major Germanic influence on US English that I can think of is Yiddish.

As for Corded Ware, that is a fascinating question. I guess the evidence from genetics is currently against such an explanation, as there were major population changes across the region. However, the problem of southern Europeans such as Spanish with IE hasn’t gone away yet. Whichever way round it turns out to be, substrate influence in Germanic, indeed many forms of, IE still seems highly likely.

Ned