A discussion of whether the Sanctuary, Avebury, was the site of a roofed building or of free-standing timber posts (as archaeologist Mike Pitts and others now say).

In 532 AD, after the second Church of the Holy Wisdom in Constantinople was severely fire damaged by rioters, Emperor Justinian commissioned a startling replacement. In just over five years the new church was built, and to an astonishing design. Its mighty space, encased by arches and semi-domes, culminated in one huge dome. It soared over an empty space so big that worshipers must have gasped to watch birds fly high above them beneath such a dome.

But all was not well. Increasingly desperate attempts to buttress the outer walls failed to prevent the dome’s collapse just twenty one years later. After another five years builders managed to restore the dome but at some cost. The pillars that supported the dome were of elephantine proportions and the church, now having less windows, was strangely gloomy. The building was still great, but perhaps not as great as before.

Enough of that. Let’s turn to the subject at hand.

William Stukeley's drawing of the Sanctuary, showing the stones still present, although the wooden posts are long gone.

What is the Sanctuary, Avebury?

About half a kilometre from Avebury, there is a flat area of ground on Overton Hill, overlooking the Kennet River Valley in Wiltshire. Up until three hundred years ago it held a double ring of stones, given the name “the Sanctuary” by the antiquarian William Stukeley. They weren’t the most impressive stone circles compared to their big cousins at Avebury. However, they had stood there since maybe 2500 BC, and their destruction by eighteenth century farmers in order to build walls and barns was still tragic.

In 1930 Maud Cunnington, famous excavator of Woodhenge, relocated the lost site of the Sanctuary. Given permission, her small team thoroughly excavated the site over a couple of months in 1930. Her methods were moderate for the time but terrible by modern standards. There are virtually no photographs, few recorded finds, only sketchy plans and just one trench section (that not hers).

Map of the Sanctuary, showing positions of posts (black dots), holes (circles) and stone holes (rectangles) (based on Pitts, 1999)

Her views about the site were fairly straightforward. The Sanctuary had contained the evidence not just of stone circles but of numerous rings of timber posts, all forming rings within rings. As at Woodhenge, she interpreted these, quite simply, as a sort of wooden Stonehenge, open to the sky. Her cousin Robert, also on the dig, interpreted the site instead as a large, roofed building.

And so began a debate that rambles on today; were the wooden rings open or were they roofed? In the 1940s and 1950s the tendency (led by Stuart Piggott) was to view the Sanctuary as a succession of roofed buildings. In the 1980s the pendulum slowly swung. Now most archaeologists believe that the Sanctuary was unroofed.

Mike Pitt’s argument

The linchpin of the current, “unroofed”, view is the exemplary re-excavation of part of the Sanctuary by Mike Pitts in 1999. I have no idea what his views on the roofed/unroofed debate were before he went to dig. His intentions, as expressed in his work, were to clear up confusion between the published work of Maud Cunnington and the unpublished Diaries of one of the other excavators on her team, William Young. Whatever their differences, he also came away from the excavation clearly seeing the site as unroofed.

The basis of Pitts’ argument is this.

Maud Cunnington’s belief was that her excavations had stripped the site down to undisturbed bedrock. In the process, she revealed rings of circular or oval holes in the chalk bedrock. The material excavated from these holes consisted largely of chalk packed back into the holes.

However, each hole also had evidence, in the form of black soil, for the rotted remains of at least one wooden post. These remains are known as post pipes. In two of the rings the holes are noticeably oval and some of these contain two post pipes. Both Cunnington and Young stated that these post pipes, where it was possible to see chronological relationships, were contemporary with each other.

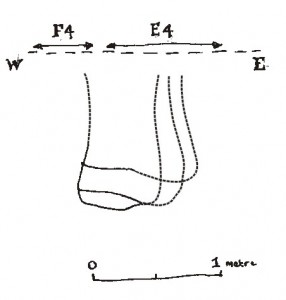

Mike Pitts, by chance, found that two of these oval holes contained small bits of unexcavated fill. When he excavated this fill he found solid evidence that the holes had been cut, partially filled and cut again in relatively quick succession. This suggested more than one phase of use of the hole. But even just by looking at the hole profiles it was clear that holes must have been cut and recut several times. The now legendary hole pair F4/E4 showed evidence for at least five phases of hole cutting.

On the basis of these holes Mike Pitts argued that the posts were part of a “process”, where posts were put up, left for a few years perhaps, then removed and replaced. This replacement must have happened at least five times to account for the five phases of hole cutting. If this were the case, he argued quite reasonably, then it would be impossible to have these posts supporting a building as well.

Mike Pitts’ story may well be correct. However, it contradicts Cunnington and Young in just one important respect (as Mike Pitts admitted); Cunnington and Young both said that post pipes, where there was enough evidence, were seen to be contemporary. In order to accept Pitts’ argument you seem to need to disagree with the original excavators.

Room for re-interpretation?

Or do you? What if you reduce the number of phases of hole cutting to four? You could do this by saying that the last two holes in the F4/E4 complex were cut at the same time and that a post was placed in both of these holes simultaneously. These two posts were never removed, and were therefore recorded as post pipes during excavation. In that case you can have both multiple phases of post placement and removal, as suggested by Mike Pitts, and the last post pipes being contemporary, as stated by Cunnington and Young.

But this is where I can see an alternative to Pitts’ Process. What if everything that Mike Pitts says he thinks happened did happen but for a different reason. Here, for example is an alternative scenario (not necessarily right, but an alternative).

A hole is dug, big enough to put in one big post. The post is inserted and packed in with chalk. For some reason, the post gets pushed over. The hole is redug, maybe at a slight angle this time. The post is put back in again. Chalk is again packed around it as hard as possible. Still the damn thing gets pushed over.

“Alright lads. Let’s try another method,” says the foreman.

This time the first hole is filled in and two new holes are dug either side of the first hole. The original pole is inserted in one hole at a very slight angle and another, thinner post is put in the other hole, also at a slight angle so that it touches the first post. The two are bound together at the top. This structure is much more stable. This time the post pair does not get pushed over.

“Job well done,” says the foreman, going off for whatever passed for a tea and smoke equivalent in the new stone age.

The above process could have taken a few hours, a few days or over a number of years. Either way, the posts are replaced quickly. But what was causing the poles to get pushed over in the first place?

The roof that was resting on them of course. Whatever the original shape of the roof, the elegant struts that were put in to support it simply weren’t working. Hence a more elephantine structure was the only way to hold the roof up. What you have is an inelegant solution to a basic engineering problem.

Now I have no way of testing whether this idea is any more right than Mike Pitts’. However, if it is a reasonable alternative and no-one can state an obvious flaw in it (comments please) then Pitts’ process is not enough evidence to argue convincingly for an unroofed structure.

I am well aware that people four thousand five hundred years ago did not think like me. They may have chosen to erect rings of free standing poles at enormous physical cost, only to replace them a few years later (for comparison look up the Shrine at Ise, Japan). However, I find the picture of a architectural bodge job, like what happened in Constantinople three thousand year later, quite human.

References

Pitts, M 2000, Hengeworld, Century Books, pp409

Pitts, M, 2001, Excavating the Sanctuary: New Investigations on Overton Hill, Avebury. Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, 94, 1-23

Pitts, M, 2000, Return to the Sanctuary, British Archaeology, 51

Mainstone, R.J. 1988, Hagia Sophia: Architecture, Structure and Liturgy of Justinian’s Great Church, Thames and Hudson, pp20

Ise Grand Shrine, wikipedia entry

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

Hi Ned,

Nice idea and interpretation. We’ve spoken about the roof before and I like your proposal of having to bodge the structure to get it to stay up. I wonder if there were different phases and trends of wooden roofed structures being superceded by open stone henges?

Are you going to write anything about your ideas on trade and Windmill Hill?

Mark

Dear Mark

Thanks for liking the idea. It’s certainly possible to have different phases, and that seems likely seeing as things do change. However, I could just about (at a squeeze) envisage putting the whole lot up at the same time, although I might be difficult to get around (see Hengeworld). But the Sanctuary’s location on an exposed hill top, if open to the wind on the west side, might make it an excellent mortuary house, as suggested by Aubrey Burl, so it may not matter whether it was difficult to get round anyway.

I’ve written a little on the Windmill Hill stuff but not yet put down the main ideas. But, hmm that gives me an idea for a post I could write soon.

thanks for the comment

love Ned