Discussing a forty years old theory of the rise of civilisations due to population pressures in restricted areas and why I think it’s half right.

In 1970, the 43 year old curator of the American Museum of Natural History, Professor Robert Carneiro, published a paper containing a theory for why states rise in certain areas of the world.

In 1970, the 43 year old curator of the American Museum of Natural History, Professor Robert Carneiro, published a paper containing a theory for why states rise in certain areas of the world.

Carneiro had done a fair amount of fieldwork in the Amazon and had started comparing the lack of cities there with the concentrations of cities in places like Peru and Mesoamerica. His explanation for the difference, Carneiro’s Circumscription Theory, can be broadly summarised as this:

Carneiro’s Theory

The rise of states in certain locations in the past was due to three factors: 1) environmental limitations, 2) population pressure and 3) warfare.

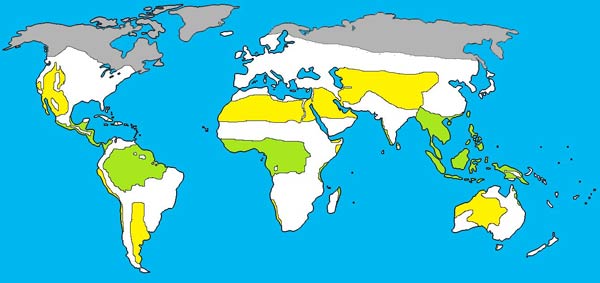

To explain. Environmental conditions allow either agriculture or don’t (although there are gradients between). States all arose in places where there was limited (or circumscribed) agricultural land. For example the Nile valley is bounded by desert, Mesopotamia by desert and mountains, Crete is bounded by sea, Inca states by high mountains and desert, etc.

Population pressure resulted from the gradual expansion of the population to a point where it reached a limit. This is when there was insufficient food to feed everybody from the limited agricultural land available. This resulted initially in people’s attempts to improve the land but ultimately could not prevent a population crisis.

Warfare resulted because there was nowhere else for people to go to reduce the population pressure. Therefore people had to turn and fight for resources. This warfare lead to individuals taking control and inevitably resulted in the rise of chiefdoms.

So goes the logic.

General criticisms

Carneiro’s type of view, that the rise of civilisations was inevitable in the right kind of geographical location, is shared by many current scientists and ‘scientific’ anthropologists. Jared Diamond, for example, advocates a great deal of luck in the origins of agriculture and civilisation.

However, like original sin, such a view implies that all the people in any area can do is wait and see whether civilisation will happen to them. Such inevitability galls many more ‘humanist’ anthropologists, who see people as more sophisticated and more involved in their own destiny than that.

Many archaeologists also also argue that the evidence shows civilisation’s spread by a process of ‘diffusion’. While the seed of a civilisation may have started in one place it then spread outward from that place through contact with more and more distant people. While diffusion doesn’t explain the ultimate origin of civilisation it does (sort of) explain that spread.

My criticisms of Circumscrition Theory

I do not believe that any early civilisations were particularly circumscribed. Egypt’s and Mesopotamia’s populations were perfectly able to head south or north along their river valleys. In fact all the evidence (e.g. the spread of Ubaid pottery along the rivers of Mesopotamia or the semi-nomadic nature of early peoples on the Nile) suggests that they did so. They undoubtedly would have had to fight someone for the land further up river but this is nothing unusual when heading into new territory.

Also, the island of Crete is sited as an example of circumscription, being bounded by sea and with limited agricultural land. But why not pick islands such as Corfu, The Isle of Wight or Tasmania? Whilst not wishing the do down the early people of these islands, they were not, unlike Crete, the originators of great civilisations or chiefdoms in the past. In terms of agriculture I don’t see much difference between Crete and Cyprus, yet only Crete developed an early civilisation.

And this brings me to the last point – the assumption that the sea is some sort of dead end. As far as can be told from archaeological evidence it was quite the reverse by the time that the first civilisations arose. If anything it was a highway. Whilst the land may have run out there was nothing stopping someone from getting on a boat and going somewhere else.

My likes of Circumscription Theory

What Carneiro did recognise is the peculiar location of the first civilisations. The civilisations of Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Indus valley, Mesoamerica and even Peru were indeed confined to small areas of land. His attempt to explain this by human processes seems a very reasonable one to me.

However, I would argue that the lands that he talks about were not circumscribed but only confined along one axis (of two, the world being sort of flat locally). With the possible exception of Mesoamerica, all were ‘long and thin’ civilisations, with agricultural hinterlands spread out in a line along rivers or mountain chains and boxed in on both sides by deserts, forest or mountains. At either end they reached either belts of fertile land or the open sea.*

Corridors corridors corridors

(As I’ve mentioned before) Linear confinement of people into corridors of land is, to me, the most important reason for the rise of early civilisations in particular locations. Like Carneiro, I’d say this seems to be the result of restricting people’s freedom of movement. Unlike Carneiro I’d say that it didn’t stop people moving along the corridors of land. Their reason for movement would often have been trade.

So, for an ancient trader trying to get from sub-saharan Africa to the Mediterranean which route should she have chosen? There weren’t many. For a traveller on foot trying to get from the bottom to the top of South America which route would they have been forced to choose through the middle? For a spice-merchant trying to get from the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean which route could they have picked? For a man with a gold-laden llama trying to get from South to North America which route might he have been forced to take?

Each merchant in ancient times was forced to choose the path that was possible – the route that prevented early death. This, of course, depended on the transport technology at their disposal. For example, a journey by sea is best only if you’ve invented a boat that doesn’t sink in rough conditions.

Therefore if that trader from Sub-Saharan Africa had had a 4×4 she would have crossed the Sahara Desert. However, not only did she not have a4x4, she didn’t even have a camel. So she went along the Nile valley. If she’d had a camel she might have used a different route. And that foot traveller would have flown across the Amazon in a plane if there’d been a plane. However, he only had his feet so he walked by the best route available, along the spine of the Andes.

I could go on. I probably will.

Reviving Circumscription

Robert Carneiro spotted something important in the geography of civilisation. Strangely, his work has been largely disregarded by archaeologists, which I think is a shame.

At the time Robert Carneiro had his insight I was learning how to use a potty. It took me another thirty years to notice the same thing that he did. When finally I did I came to a very similar conclusion to him. Ten years later I think the evidence shows something more interesting.

I believe that the ‘scientific’ view of the rise of cities and civilisations, as argued by both Diamond and Carneiro, is useful, but is too much of a simplification. This is probably why many archaeologists have junked it.

A ‘scientific’ view does not take human nature into account and the complex stimuli that make people do different things. It misses all those subtleties like people’s innate desire for shiny things… or wanting a better life for their children… or to outperform the neighbours… or for young people to seek thrills. Without this any scientific model is dry and lifeless.

I suspect that the evidence shows civilisations arose where there was a concentration of people passing through narrow corridors in the landscape. I don’t really have a good understanding of why cities should have arisen there because of this but I think they did. I’d guess it had something to do with trade. It very likely also had something to do with warfare.

Whatever attempts at explanation I come up with will be guesses and will probably turn out to be wildly wrong, like I suspect Prof. Carneiro’s are. But Carneiro at least recognised that there really is a pattern to the distribution of these early civilisations, something which many seem to ignore.

References

Carneiro, R.L. 1967 On the Relationship Between Size of Population and Complexity of Social Organization. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 23, p234-243.

Carneiro, R. L. 1970 A Theory of the Origin of the State. Science 169, p733–738. (alternative version here)

Carneiro, R.L. 1986 The Circumscription Theory – Challenge and Response. American Behavioral Scientist 31, p497-511.

Kemp, K. W. 2004 Carniero’s Circumscription Theory on the Origin of the State. web page.

(Rivers image adapted from The Why Files’ Water Woes webpage)

*I’ll abstain from any comment about China as I don’t have enough info – any comments gratefully received.

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

I have had a long-term interest in Carneiro’s theory of the origin of states and when I read your comments on the theory they rekindled interest in the whole problem of the origin of states. I remember Carneiro’s article in 1970 and I was electrified by it. I have wondered since why there was such a dearth of professional interest in the theory. I read Robert Graber’s book about the theory with the same wonderings. I think ignoring Graber’s work is even more puzzling. I am not prepared to provide comments at this point, but I really would like to see the main issue (the rise of the state) treated in good scientific fashion with lots of discussion and comment (and of course analysis of data), In my view, the main issue is FUNDAMENTAL for ALL social sciences.

Mel Barber

Thanks, Mel Barber, for citing my work, which interprets circumscription theory mathematically as the proportion of population increase that takes the form of density increase rather than areal expansion. Political evolution is predicted to take the ideal form given by N’ = 2P’ – A’, where N is the number of autonomous polities of any scale; P is population; and A is area inhabited. The apostrophe denotes proportional growth rate.